Royal College of Art MA Dissertation, 2009

She hovers between worlds, hybrid and fragmentary, a fire-breathing chimera whose being is grounded in the oscillatory. She is incomplete, as such assuming immunity from the conceits of the delineated ‘one’. Rather, her presence constitutes oneness in itself; a Klein bottle with infinite folds ceaselessly navigating the depths of their native dimensions, whilst in an instant exposing the opaqueness of the plane to which all things are bound. Her things, her inventions, are born beneath these folds. Perceptible for the most part as similar to all else, they reveal themselves through oscillations, slippages, to embody a subtle yet inescapable quality of not-quite-thereness.

I first encountered W through her dreams; her lupine fantasies drew her, though what drew them, or knowledge thereof, perhaps cannot be approached. Something like the creative soul, she would say, yet I am more inclined to believe in a blind, chaotic emergence. In any case, like Chuang Tzu and the butterfly, in the here and now she loses the freedom to inhabit an unquestioned place in the world. Her memory is slight, resisting a lucid insightfulness, but her rarity lies in an unaccountably porous condition of being, permitting something of her lost state to seep through, manifest in her material creations.

In her forest of images, a Lapland idyll beneath the Aurora Borealis, her fellow wolves reside, continually standing guard over a small clearing in the trees. At the heart of this clearing there lies an Aleph. The Aleph, she implies, is a point at which all points of the world converge; time and space reveals itself from each and every conceivable and inconceivable position, focused in an instant upon a singularity. W’s privileged position amongst her pack grants access to this thing of things at will whenever she may wish to gaze upon and within it. However, it would appear as though these frequent encounters pass her by as if unnoticed, although what is clear is that some residual knowing remains immanent to her being.

Whilst to date I have not had success in gleaning from her directly more than the most rudimentary of descriptions of this anomalous node, I have been able to uncover an account of such a thing elsewhere:

The Aleph was probably two or three centimetres in diameter, but universal space was contained inside it, with no diminution in size. Each thing […] was infinite things, because I could clearly see it from every point in the cosmos. I saw […] the circulation of my dark blood, saw the coils and springs of love and the alterations of death, saw the Aleph from everywhere at once, saw the earth in the Aleph, and the Aleph once more in the earth and the earth in the Aleph, saw my face and my viscera, saw your face, and I felt dizzy, and I wept, because my eyes had seen that secret, hypothetical object whose name has been usurped by men but which no man has ever truly looked upon: the inconceivable universe. (Borges, 130-131)

![]()

Freedom sits quietly on my wall in a corner seldom frequented by visitors. A painting, modest in size (barely one by one and a half feet), it abstains from any spectacle, refusing to clamour for the attentions of the eye despite the numerous surrounding pictures of imposing scale and stature that would presume to engulf it. It stands its ground, within its ground, passing over itself with silent content. Monochromatic, the canvas is flooded with a particular hue that escapes effective categorisation. Viewing its surface at present, it appears to most closely resemble a shade of teal green, although as I write I must observe this statement to be wholly unsatisfactory. Attempting to pin down any actuality appears to result in her colour shifting as if to perpetually elude one’s descriptive powers, to refuse apprehension. An image emerges, though not out of any fixity of form, but through an intuitively discernible nature. I see a vision of a solitary horse, in profile, moving across the plane of the canvas from right to left.

She has neither quite reached a gallop nor a trot, but seems to act at her own pace, frozen in the beginnings of purposeful movement, an uninterrupted becoming. W says her movements are an embodiment of a freedom “neither to be there, or to be not”.

![]()

Caltha Palustris, commonly known as the Marsh Marigold, blooms with vivid and pure yellowness. Yet the colour of this flower can equally and simultaneously said to be purple, or rather Bee’s Purple to be more (or less) precise. The pigments engrained in its petals are composed such that as humans we can have no corporeal perception of their colour, for they have been evolutionarily designed solely to seduce the ultra-violet sensitive vision of honeybees, escaping the limits of our own vision’s spectral capacity. A blend of yellow and ultra-violet wavelengths, this colour presents itself to us as incomplete, simply as yellow, but for the bees it glows with what we can only speculate in our terms to be a sort of purple iridescence. As such, it lies in a state that we may gaze upon, but ultimately cannot see. One can acknowledge it as that which is other than it appears, a logical sense that exceeds experience, but it is not within our semiotic vocabulary or imaginative reserves to conjure up for comprehension that unseen trait of the real, despite a command of nature that permits us to pluck this petal from its stem for thorough tactile scrutiny or, furthermore, to devour it.

The Marsh Marigold is thus a metonym for the material world, acknowledgeable for its surplus, but forever fixed beyond our grasp, revealing only fragmented form from within the confines of our individual perceptive spectral ranges. The condition of Freedom, however, is of an exceptional order in that it apparently needs no such prior knowledge of exteriority in order to be acknowledged as appearing as other than that which is and can be seen. Rather, its not-quite-seenness thrusts forward from within, insistently permeating one’s perception instantaneously; comprehension that precedes apprehension. Any knowable pictorial grounding of sense, of colour and of form, is subsumed by the sense of the image, of affect, that radiates a presence that evades signification. It is image that is distinct from the world. It “exceeds the phenomenon in the phenomenon itself” (Nancy 1997, 17), receding into itself, thrusting forth presence in its own ontological absence.

![]()

The status of ground within art might assume that of the plane of formlessness to which the real is bound. It is a state that must be withdrawn from reality, enabling the foundations of figure, of language and experience, but lost in the actions enabled therein. The real lies outside of language and experiential reality; it is “that which resists symbolisation absolutely” (Lacan 1988, 66). “There is no absence in the real” (ibid. 313), for it is a mode of pure presence, a realm of unmediated force and becoming “absolutely without fissure” (ibid. 97). The formless constitutes the ultimate state of existence, amongst which the actuality of the unconscious self resides; “I think where I am not, therefore I am where I do not think” (1977a, 177).

Figure functions as an instigation of reality, and is thus of the order of the symbolic. Perpetually encircling the formless plane of the real, the symbolic order attempts to enact a reality of coherence by way of designating an order of things. This is the level at which pictures are formed, and so we may say that the symbolic is thus a register enabled by the differentiation of signifiers. The abstract, on the other hand, may be defined as this differentiation in itself. It is the obverse of the real, for it is that which can have no concrete substance. Its ontological condition is that of the immanence of language; that which resists objectification absolutely. The abstract is language outside of linguistic process; signifier without signified, sense without object.

‘Abstract’ as an entity is therefore oxymoronic as a tangible thing in of itself, for, in order to be a thing, it needs to be situatable within reality, thereby negating itself as abstract. The excess necessary for the image (as sacred/distinct) to be induced does, nevertheless, necessitate a form of abstraction in order that a sense (of the world) may be engendered. This abstraction must avert the tautological condition of pictures, the paradoxical cycle that has to be overcome by the artist—a seemingly impossible undertaking. The loophole necessary for such an escape may, however, be enabled by the Gödelian dictate that all systems must in fact be incomplete in order that they may be whole. Perhaps this incompleteness lies at the heart of the creative self, a fracture that permits a crossing between worlds and brings about creativity. It is not by attempting to create the abstract that abstraction and presence are achieved, but rather art must entail a process of abstracting the presence of the ground from the figure of reality itself. One may ‘touch’ this ground only by sensing the immanent difference from which the image recedes.

![]()

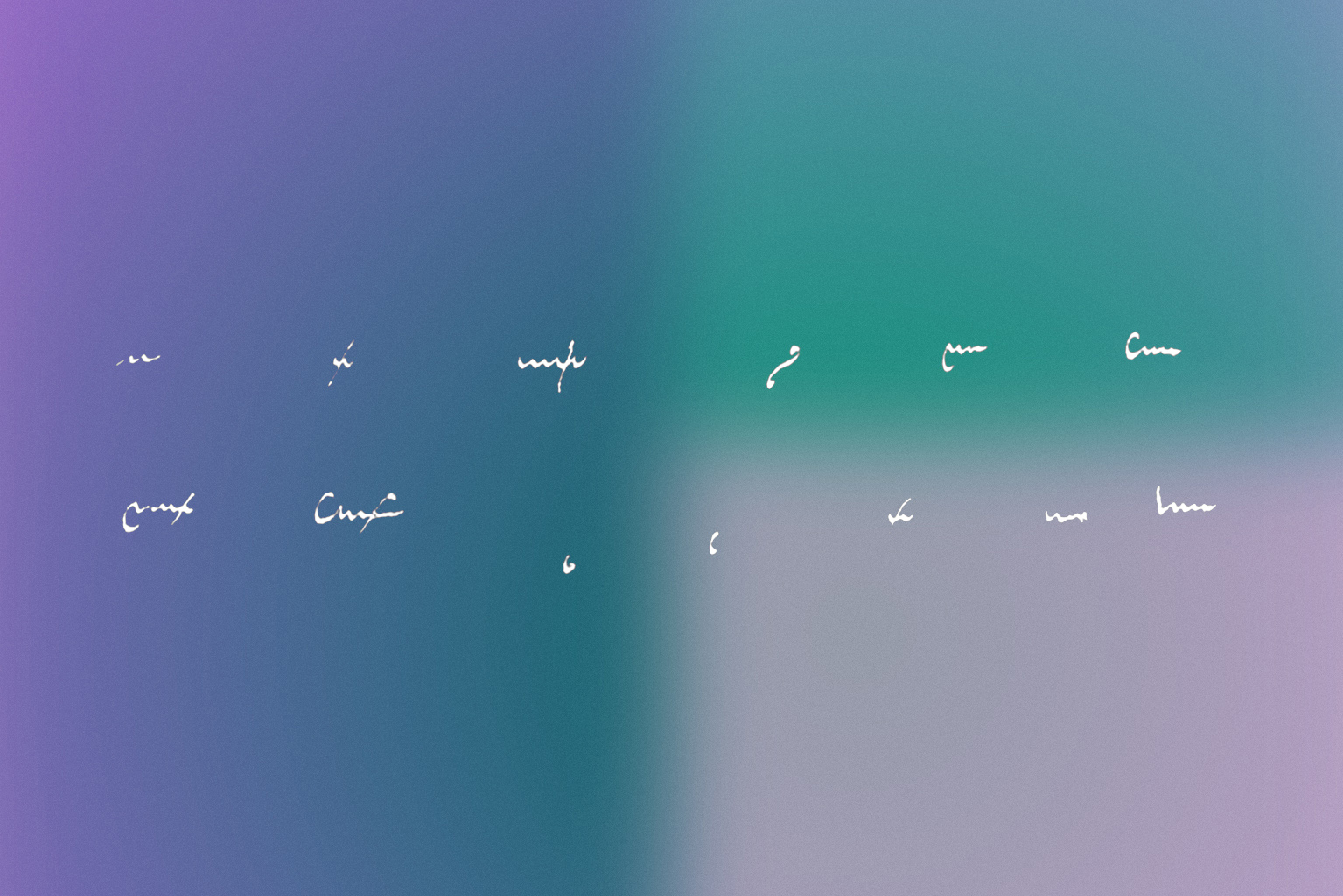

Gerhard Richter’s aleatoric installation, 4900 Colours (fig.i), is a multi-panel painting consisting of 196 segments, each measuring 48.5 by 48.5 centimetres and comprising 25 individually coloured squares. A palette of 25 colours is used throughout, seemingly selected from the full reach of the chromatic sphere. These belong to the approximate orders of red, white, green (of lime and British racing varieties for instance), grey, yellow, navy blue, purple, orange, black, and so on. The colours are distributed amongst the 4900 squares according to an abstruse system instigated by the coming together of chance, the mathematics of the magic square, and the internal logic of the artist’s whim (further details of which need not be visited here). Furthermore, the 196 panels can be configured in 11 variations that range from a single large-scale contiguous piece, to multiple smaller segmented configurations of varying sizes (for example the 49 identically-sized panels of 100 squares, as exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery, 2008). As Peter Gidal observes, the work’s constituent colours are “like colours not seen elsewhere, or rather, unlike colour seen elsewhere, not reminding of a semiotic activity elsewhere in the world, that of art not excepted” (Gidal, 96). That the colours cannot be placed, appearing to be neither the colours of nature, nor the extracted or signifying colours of graphic or visual construction, leads one to envisage a third, more enigmatic status, akin to that attributed to Freedom.

figure i: Gerhard Richter, 4900 Colours (detail), 2007

Such a condition here, however, would not appear to present itself simply from within a single instance of colour, or any given individual square’s inherent tonal value. Rather, the affective trait one may encounter arises from the inter-relational functions of each constituent part, and it is clear that it is as such not simply a colour but an image that thus springs forth. Neither the single block of colour nor the whole matrix of coloured squares constitutes an image in itself, rather the image as heterogeneous entity is wholly dependent on the oscillations perceived within the artwork in its entirety. These oscillations act to seemingly transfigure the individual colours into those that would appear to be outside of semiotic activity, the colours’ interactions inducing a presence that alternately surfaces and submerges beneath the patchwork sea of colour. The individual component coloured squares thus do not act as the figure of the image, but rather are engaged in a becoming ground to which the image recedes and attains the status of the distinct. Through the processes of art, the sense of this image may be said to be graspable as a trace of that which exists outside of worldly semiotic activity. One may perhaps go further and invert this view to articulate the image’s embodiment of semiotic function’s very essence. Not simply born out of difference, rather, a possibility surfaces that brings forth difference in itself as pure presence.

![]()

“Only in the dance do I know how to speak the parable of the highest things.”

(Nietzsche, 121)

She is a dancer, she insists. She dances with her colours, instilling movements throughout the fields she roams. She is compelled to do this, not out of ambition, but out of the pains of an intangible excess.

![]()

An evasiveness or continuous deferral, the refusal to be pinned down, is the very nature that shapes difference, and thus affect. Music is rich with such difference for it is in itself comprised of nothing more or less than opposition and oscillation. From the outset, the material oscillations that instigate music’s physical mediation—the vibrating strings of the violin or piano, the reeds of the oboe, the singer’s vocal chords—shape the movements and suspensions integral to music’s functionality. Potent examples of music’s affectiveness (particularly within what is termed ‘pure’ or ‘absolute’ music, rather than the programmatic types) can be attributed to instances of superlative evasiveness. The ubiquitous blue note—that musical feature so integral to African American music and its countless offshoots—is a case in point. To be truly blue, the blue note cannot be induced simply as a single formulaic dissonance. It cannot be effectively written, fixed or thought of as a segregated moment. It is rather a movement, a becoming blue, revealing the image of the minor sliding in oscillation against the major and vice versa. The blue note passes through the symbolic register, imbuing a sense of presence of the real, for it dances resolutely on the register of the formless.

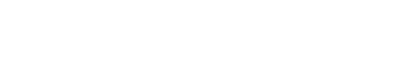

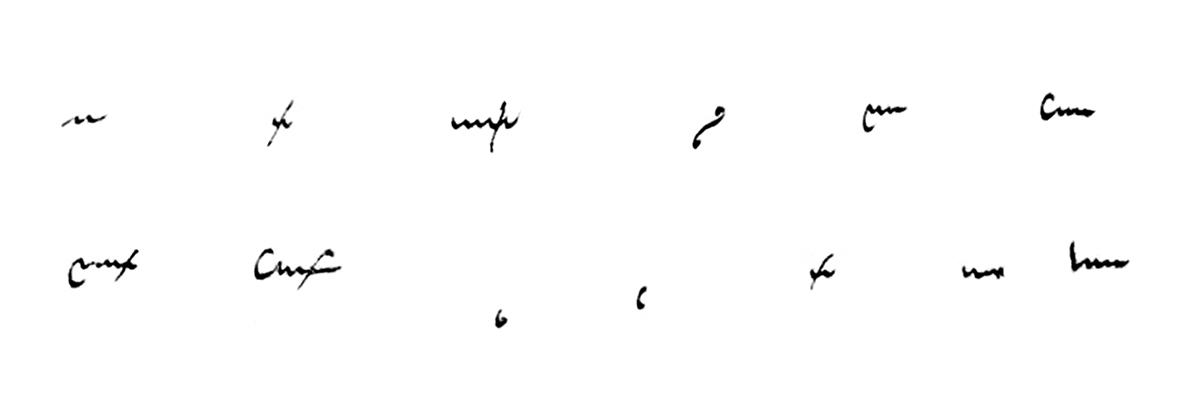

figure ii: Ornaments written in J.S.Bach’s hand, taken from the guide to ornamentation included in the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, c. 1720. For the purposes of this illustration, all details except for the ornaments themselves have been obscured.

The quivering ornamentation that floods the music of the High Baroque is equally pertinent here. The elaborate trills, mordents, turns, appoggiaturas and acciaccaturas especially prevalent within keyboard music of this period were not simply used as a means of evoking deeper hues of tonal colour by way of embellishment—colour already present one could say at each step of the chromatic scale—but rather they function as if to induce a colour not bound by the spectrum’s form or its formal possibilities. The line of the music can thus be brought forth beyond the surface of modal context, for such movement instigates affect, effectively drawing out the line of the line from within its folds. The rigour of the application of notation designed to guide the performance in the way of such immanent oscillations perhaps belies the character of the sought after affect. However, that such notations often resemble the traces of earthworms or spiders squashed underfoot might be seen to allude to the true nature of this unsignifiable (fig.ii).

A motivation shared by many of the devout composers of Bach’s day was the desire to attain a realisation of divine order, to hold a mirror up to the ‘absolute’ music of the heavens that, in their view, would transcend that which was possible within the worldly confines of material existence. Indeed, Bach’s final great composition, the unfinished Die Kunst der Fuge (1750), was arguably written with the intent that it should not be physically performed, for through performance the ‘absolute’ quality of the music would surely be tainted by the imperfections of physical mediation (owing to the inconsistencies of the performer, the impossibility of perfect temperament, etc.). Instead, one was encouraged to bypass and surpass the limitations of the material world by means of a purely cerebral performance, enabling a comprehension of the divine in the mind of the beholder. From a secular position, however, disregarding the standpoint that puts its faith in a metaphysics of transcendence, one can rather redirect the concept of such divine order towards a metaphysics of immanence. We can see such artworks as not simply attempting to reflect an idea of that which lies within, but rather they can be seen as enacting a becoming of the pure difference and unmediated affect of the immanent and formless real itself.

Within the history of tonal music, Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 in D major (1909) perhaps grapples with such processes most vividly. Written at the very end of the composer’s life, the culmination of the work can be seen as an attempt to push through to a beyond, one of an immanent tonality, and so to illuminate and touch that which one imagines he perceived to be the very essence of life. The climax of the symphony arrives midway through the final movement, whereupon the melodic line becomes subjected to dizzyingly intense tonal undulations, progressing through near-endless modulations. It is as if, with the entirety of western musical history driving it forward, a line of flight is set loose, searching for perfect resolution in some mysteriously formless and unfathomable key that would lie at its core.

The tonal thread can be felt to subject itself to an almost deluded self-mockery, seeking a modality that would surpass that of any formal harmonic centre (i.e. D-flat major) from which a resolution of absence might be realised, averting the unsatisfactory partiality of conventional tonal resolution. Such a key could not be encountered directly, but instead finds presence through allusion, induced by the tonal oscillations of relentless modulations. The point at which this becomes most tantalisingly within reach comes about immediately prior to a complete collapse, brought about by the overbearing weight of sublime presence that has come to exhaust its own flame of affect. What remains is a deconstructed singularity, a monophonic line played in unison by the strings, which, rather than proceeding to carry out the anticipated resolution,

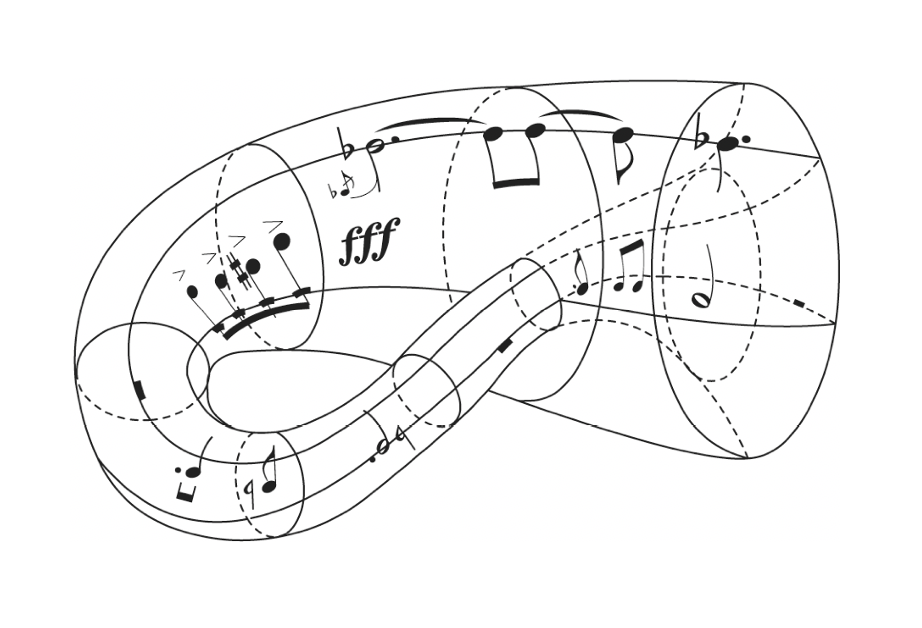

effectively signals something more akin to an inversion of commencement, petering itself out into a sonic abyss (fig.iii). In the words of Leonard Bernstein, this moment “is terrifying, and paralyzing, as the strands of sound disintegrate. […] And in ceasing, we lose it all. But in letting go, we have gained everything” (Bernstein, 321).

figure iii: A visualisation of bars 121-123 of the final movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, as if transposed to a speculatively formless register.

![]()

The Mocking of Christ with the Virgin and Saint Dominic, a fresco by Fra Angelico (c. 1440), occupies the wall of the seventh cell of the upper floor of the San Marco Convent in Florence. Created not as a work for public consumption, rather, the painting is situated alone within this compact space for the sole purpose of serving as a focal point for private monastic meditation and prayer. It thus dispenses with any superfluous detail or decoration, instead presenting a highly symbolic construction of bare and elemental forms. At the centre of the frame is the figure of Christ, dressed in white robes and seated upon a simple red form. This seat rests upon a raised white platform, beneath which sit the two witnesses, the Virgin and Saint Dominic. Their backs to Christ, their bodies are turned outwards towards the viewer, to the beyond of the frame, emphasising their role as “intermediaries between humanity and divinity” (Scudieri, 60). Their faces, however, remain turned away, engaged in acts of contemplative absorption. The figure of Christ appears similarly absorbed, for, blindfolded, he sits with regal dignity, unmoved by the acts of mocking to which he is being subjected. Symbolically presented in this single frame as synchronous events, the disembodied limbs and faces of the perpetrators inflict upon Christ acts of spitting, smacking and beating with a stick, the crown of thorns having been placed atop his head.

Set against the wall behind Christ is a flat pale green rectangular backdrop, the cool but vibrant hue of which dominates the otherwise muted palette of the composition. This green would seem to be responsible for bringing into being an action, a mystical becoming; an artificial ground to which ‘divine’ operations might be allied. The relationship between this element and the three groupings of figures is pivotal to the experience of the work. The group of disembodied figures that mock Christ float, seemingly lost, in front of this green, whilst the two witnesses at his feet feel its weight as a monolithic presence, acting as a gravitational field that pulls in the direction of the unseen imaginings of their averted and absorbed gazes. The figure of Christ, however, appears to be caught up in an emergence from and to this ground, as if able to cross at will the boundary between the world of reality and the world of formless ‘divinity’. Christ signals the bringing forth of this formless condition.

One final aspect of this painting that is striking is to be found at its apex. The wall to which the green ‘ground’ is pictorially attached ends abruptly, and all that is left is a blackness. This blackness looms like the darkness one imagines can only be found upon gazing outwards from the furthest edges of the universe, and it is this black that compositionally operates most enigmatically in relation to the green beneath. This blackness offers nothing but the possibility of a point of pivot, enabling oscillations to spring one’s senses towards the ground of immanent affect drawn forth below. These relationships of opposition and oscillation are reminiscent of Rothko’s greatest canvases, which attempt to display such characteristics in a pure and distilled form. In his most effective compositions, such as No. 5 from 1964, it is not the central void that constitutes the focal point or destination of meditative viewing, but rather this space acts to engender the perception of an oscillation at the horizon of the abyss and the contrasting surrounding element, bringing into effect an affective presence of becoming.

Returning to San Marco, it is worth noting that the same green as appears in The Mocking can also be found elsewhere, most immediately in the fresco in the opposite cell (No.24), The Baptism of Christ. Here it forms the river that flows through the image in which the figure of Christ is partially submerged. The notion of flowing can be seen as a motif that carries right through the entire fresco cycle here. The stream of water in the baptism, the trickles of blood from Christ’s wounds on the cross, even the spittle thrust in his direction in The Mocking, bring about a fluid bridging of the space between corporeal existence and divinity, or in a secular sense between that of experiential reality and the formless real. This crossover perhaps reaches its culmination, its most abstracted state, in an extraordinary segment of painting that is found at the bottom of The Madonna of the Shadows, most likely the final work of the cycle to have been completed (Scudieri, 122). Here, four rectangular panels have been painted to loosely imitate the figured surface of brightly coloured marble. The peculiarity here lies in the style of their construction, for the painted surface boasts an array of splodges, splatters and flicks of paint, most uncharacteristic of fresco painting of the Quattrocento. They allude to a highly gestural mode of creation, startlingly modern in its manner. Georges Didi-Huberman speaks at length about the anomalous nature of these panels:

…this multicoloured splattering could […] be termed the pure material figure of the divine, in the sense that Johannes Scotus Erigena spoke of materialis manuductio: formless matter, if we imagine it as a figure—certainly paradoxical, certainly dissemblant—takes us by the hand and skilfully projects us toward the most contemplative regions of grace. (Didi-Huberman, 55-56)

![]()

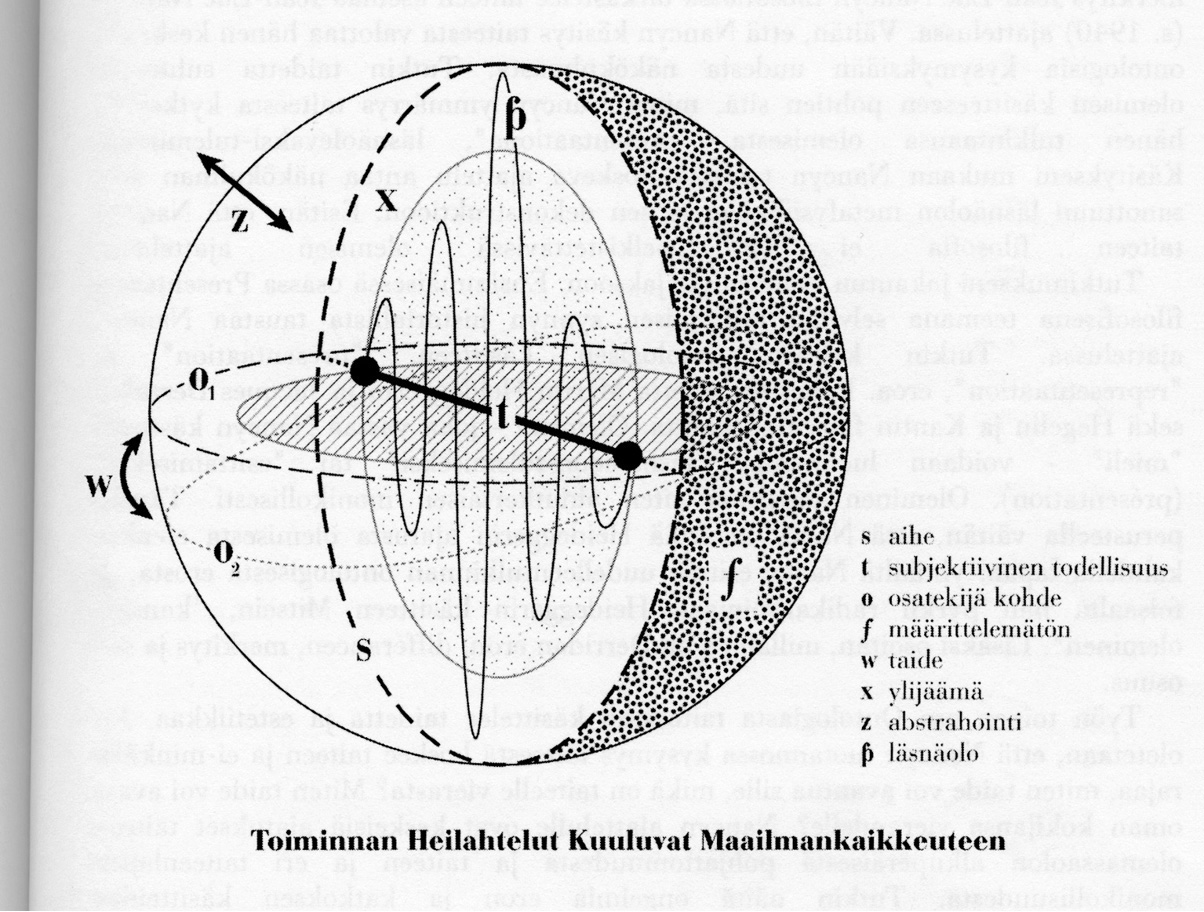

figure iv: The Diagram (author unknown)

I happened upon the diagram whilst leafing through the pages of a volume that had lain dormant, seemingly for some considerable time, amongst the small stack of books assigned the duty of propping up her bed. Whilst I could not unravel the exotic dialect of the text contained within those aged but apparently unread pages, for some reason the graphic exposition of this unknown schema (fig.iv) seemed to immediately resonate. It was as if it encapsulated a way of thinking familiar to me, though unknown; a Weltanschauung I aligned myself with, assuming an intuitive comprehension of its whole, whilst not yet having the capacity to apprehend its inner workings. I did not tell her about my discovery, for I knew my sense of understanding could only take root through an unmediated unfurling of my intuitive relation to this thing, set apart from the influence and doubt that an exterior voice would inevitably exert.

After many months spent studying the chart, attempting to decipher its arcane symbols, a coherent sense of its systems eventually materialised. It became clear to me that its sphere represented the whole of existence: the formless real [ƒ] encapsulating the world. Here the world is pictured as seen from a hypothetically exterior perspective, a viewpoint that is by definition paradoxical in nature. The absurdity of representing the ‘formless entirety’ as a sphere is also apparent, but, for lack of any less problematic alternatives, I considered that it may just as well have assumed this form as, say, that of a globule of spittle.

The interior of this sphere, then, is a space where the true substance of [ƒ] lies hidden. Along its surfaces is supported the thread of a subject [s], standing for the path of the individual, a consciousness playing the role of protagonist in a solipsistic reality. This subject operates along a cyclical corridor, attached to the formless plane of [ƒ], but is severed from any perception of [ƒ] by a cavity [x]. The subject encounters foreign elements, objects [o], as intersections along its path of existence. These objects chart a similar trajectory about the plane of formless ground, and likewise display some kind of ontological diminution by way of that same [x]. Their inner ‘deflated’ circles stand for the semiotic spaces of subjective reality. This is the place in which subjects and objects may interact by way of experiential actions: mediations through linguistic processes. This artificial interior environment, cut off from [ƒ], leads the line of interaction [t] to take effect, whereby the successful symbolic operations of phenomenological ontology may be enacted. [t] is thus in this instance the subjective reality of [o] that is created by, and belongs to the subject [s]. [s] is a part of [ƒ], as is [o]—they are of the same stuff—although they cannot gain awareness of themselves as such, due to a separation, a lack, instigated by [x]. As I shall detail, however, it would appear as though this [x] also serves to allow the operations of affect, and thus of art, to take effect.

The most mysterious figures here seem to be those of [w], [z] and [ƥ], for, I have surmised, they do not in fact represent semiotic actions, but rather those of sense. [w] serves as the embodiment of the operations of entanglement enacted between two instances of an object [o] within some sort of oscillatory machine, such as the constituent parts of a composition designed for aesthetic rumination (e.g. the elements of a painting). It is that place where the work of art is brought about in emergent oscillation or, rather, [w] is that which we might choose to term the ‘work of art’ itself. Through movements of affect—incendiary becomings of immanent difference about the axes[1] of [z]—such oscillations cause the plane of semiotic experience [t] to loosen from its taut state. [z] stands as abstraction, whose distillatory processes enact allusions to the real. Though [t] is still aligned to the orientation of the subject, at a certain tipping point it crosses a boundary into the realm of excess [x]. This tipping point is [ƥ], an oscillatory presence whose flames would soar so as to kiss the ground of the formless. [x] is thus the space of lack, but also of excess. The thread of [t] can only ever be set in elasticated motion along the axis of the subject [s], and so the point at which presence may be realised must be in alignment with that same subject’s being, as opposed to those of the objects that instigate these processes. The subject can never escape this ontological axis, but at the point at which presence is induced, the frame of this constraint evaporates for, as we have shown, at the apex of the real both [s] and [o] and all things are the same; a revelation that only [w] may induce.

![]()

She is caught between languages, her native Arctic tongue having long since escaped her logic. She has lived here for too many a year, surrounding herself always with others who share in the erosion of primary linguistic expression; those who have also come to reside here from distant lands, and by necessity may only converse in a secondary voice not of their own minds. Her processes are thus mediated by an agency foreign to her own thinking; one into which she cannot wholly assimilate her being, be it for a lack of immersion, or a stubborn clinging to the remnants of that forgotten place from which her language has been left to decay. Whatever the case, she bemoans the absence of tools by which to retrieve that original source, for time has severed the neglected arteries of linguistic germination. She thinks not in any discernible language. Only through the visions of her dreams—the traces of which are embedded amongst her things—may W’s cognitive voice of reason and rhyme flourish, for what is seen within the Aleph requires no language.

![]()

In Schrödinger’s famous feline thought-experiment, the vital status of a cat contained within a pocket of ‘Hilbert space’ is concluded to be paradoxically aligned to the aleatoric nature of quantum indeterminacy, as opposed to the common-sense concreteness that underpins the laws of classical physics. This Hilbert space, a space of pristine isolation, cut off completely from all exterior forces, is usually thought of as an abstract and hypothetical ideal, remote from the three-dimensional world of our ordinary perceptions. However, the physicist Colin Bruce details how the container necessary to undertake such an experiment—a place where this Hilbert space may take shape—might be constructed in a real world (though highly elaborate) scenario. He suggests a remote extraterrestrial setting, perfectly shielded from the interfering effects of the surrounding universe. Specifically, he details the construction of a pure steel chamber set within the hollowed-out centre of an asteroid or comet nucleus. He then proceeds to speculate about the events that might occur were a person, a ‘philosopher-astronaut’, to be the inhabitant of such an enclosure:

In theory, the space capsule now no longer contains a philosopher-astronaut, but a Hilbert space, a probability distribution of philosopher-astronauts doing increasingly divergent things, as their personal histories diverge depending on exactly how many photons hit each cell of their retinas and other quantum events that multiply into macroscopic consequences in various ways. If we could look inside the capsule (which is, by definition, impossible), we might imagine seeing something like a multiple-exposure photograph. Is the astronaut writing, or brushing her teeth, or just staring into space? […] What a Schrödinger box really contains is not one of what we originally put in it, but many. […]

We have seemingly created a macroscopic bubble of Hilbert space, in which different probability histories of the astronaut, eventually diverging quite significantly, can trace themselves out. In principle, we could do a test to prove that this has happened, using interference between the different histories. […] However, when the capsule is opened the astronaut herself will report nothing out of the ordinary—the Hilbert space will instantly collapse to a single point, selecting just one of all the possible states that it has been exploring. (Bruce, 82)

This hermetic bubble of Hilbert space might, in its distinctness, be seen as somehow detached from our existential grounding. It is, however, a direct and unmediated enactment of the formless real; a place where events emerge simultaneously, not bound by the concrete, yet fictive, solidifications of differentiation. We must see the events envisaged therein not from the perspective that creates a picture of this place as a strange and rarefied hypothetical bubble. Rather, though they seem alien to us, we must embrace such processes as those that underpin the fundamental structures of the world.

Our everyday view of the world is, nonetheless, necessarily distorted, for, in order to function successfully, we have an essential and inherent need to divide and differentiate all that is there by way of an instigation of difference and a utilisation of sets. The order of two is, nonetheless, but a fiction that must be superseded by the actuality of the one that is here. We must therefore note that the condition of collation, of all hypothesising—that is to say the whole of reality (nature, science and phenomenological activity)—lies within an anomalous bubble of deluded exteriority, ostensibly cut off from the formless ground of existence[2].

Though unbeknownst to her person(s), the philosopher-astronaut, upon entering the capsule, is dissembled to the level of an undifferentiated actuality, as if living between worlds, simultaneously pervading all modes of being. She is a simultaneous infinitude of formless assemblages; formless, even from this place of unjust linguistic fixity, for in order to be called ‘form’ an entity need possess the boundaries that such existence within Hilbert space’s unbound infinitude lacks by very definition. She thus assumes a status of distillation comparable only to that to which the work of art strives.

We can observe neither this philosopher-astronaut, nor the thing of art directly. Art alone, however, possesses the power of affect capable of penetrating the membrane separating these worlds and imbuing their sense with presence. Operating independently of any artist or observer, this thing is the autonomous excess of art. Consider, for example, the thing that lies concealed within Marcel Duchamp’s ball of twine (fig.v). An allegory of art and existence itself, it has been fully assimilated into this state of artistic dissemblance. It is the trace of all art’s things. Its sound is, perhaps, the sound of the Aleph.

figure v: Marcel Duchamp, With Hidden Noise, 1916

![]()

W’s things recede from this world, the world of signifiers and signified things, crossing a boundary punctured by their immanent excess. It would appear that the processes involved in their creation cannot be opened up to rational analysis. Her paintings are more than pictures.

She longed to fully grasp those objects, to understand the mechanisms of affect concealed therein. Though created by her own hand, manifestations of the very threads of her being, they remained frustratingly exterior to the conscious operations of her self. She saw in the camera the potential for revelation, a magical instrument with the capacity to spawn “pure image”, removed from the problematics of materiality. She encouraged me to pursue a method to capture that thing of Freedom, the sense brought about by that autonomous element of excess.

![]()

We see that painting cannot fully subsume itself to the nature of the distinct. Whether one’s encounter is one of seeing-as or seeing-in[3], the painting must always retain a distance between image and form, owing to its own materiality and dimensionality. Thus, the basis by which one might make judgements as to the quality of a particular painting perhaps rests on the extent to which it is able to negate its own form, to achieve a dissemblance that embraces the formless. Freedom achieves this to an incomparable degree, yet, though the distance therein is imperceptible, logic dictates that such a divide remains.

Paintings are always born into the condition of pictures, be they direct representations of subjective reality (pictures of objects or scenes), or attempts at ‘abstract’ or ‘absolute art’, which must nonetheless be representationally bound to an expressionistic act, or to the experiential materiality of paint. Pictures can do no more than depict reality “by representing a possibility of existence or non-existence of states of affairs” (Wittgenstein 1974, 11), and the planes of phenomenological operations—and thus any such representations—are necessarily removed from the world of excess, of the formless and undifferentiated real, by linguistic mediation. However, in exceptional circumstances a work of art may be considered not simply a picture, but what we might term a picture+, for it contains a surplus, an excess by which sense is enacted, approaching the status of image.

The photograph is itself blind to such sense in its creation; the process of photographing things and presenting a picture in order to imbue pictorial subjects/states of affairs with presence is always a fabrication, for the original, delineated things have no quality of distinctness, and thus no observable presence, to start with in of themselves. Only an image may ever attain presence. Photography does, however, possess the unique possibility of becoming pure image, for, rather than having been created afresh from formations of difference (i.e. those of paint), the photograph’s modality emerges from an immanent and latent formless state. The photograph’s advantage lies not in its form’s proximity to image (as in painting), but rather in its capacity to attain the status of image in of itself.

![]()

I sought not to picture W’s composition, the secondary thing that enacts the excess, but rather, I envisaged a reimagining, or reimaging; a method by which to directly transmit a path of abstraction and oscillation—the horse’s flight, perhaps—in order that this primary or universal thing might be presented in its distilled form; presence itself granted presence. The finality of such an image would not, however, be aligned to that of the ‘final artwork’ of modernist ideologies. Its universality would lie in the oneness, a nature of utter distinctness born in isolation to itself. Rather than operating as a hypothetical ultimate form of objective ends, it would instead entail an embodiment of a universality of subjectivity—the extent to which affect is instilled as the essence of experiential existence.

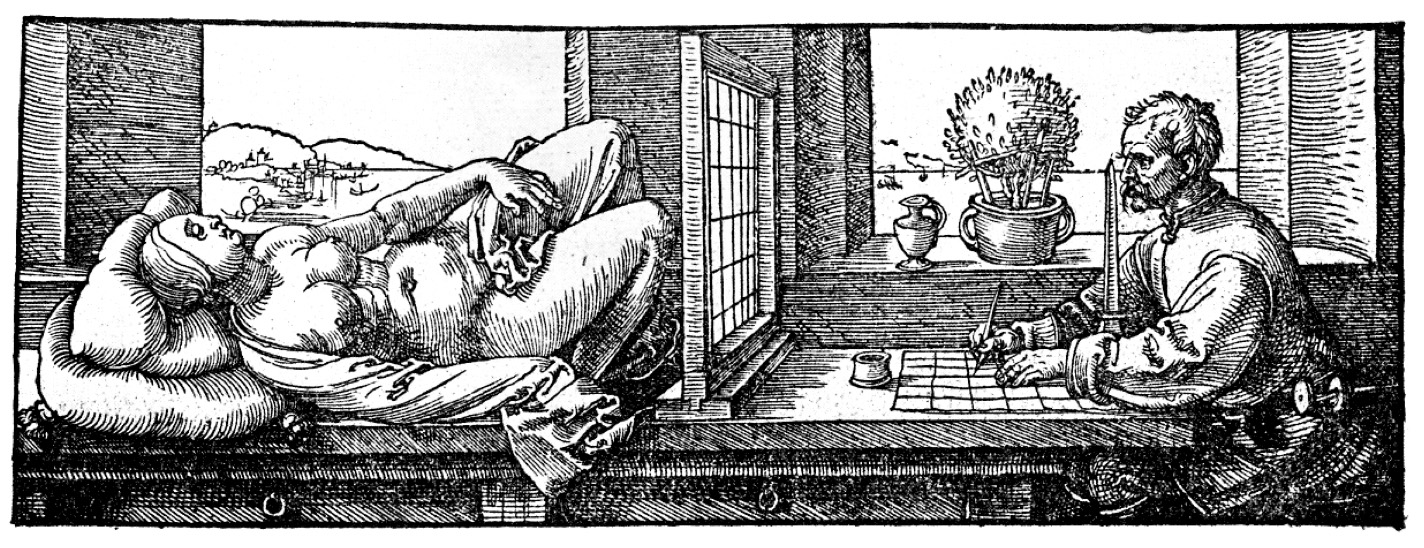

figure vi: Artist drawing a nude with perspective device,

woodcut from Albrecht Dürer’s Underweysung der Messung, 1538

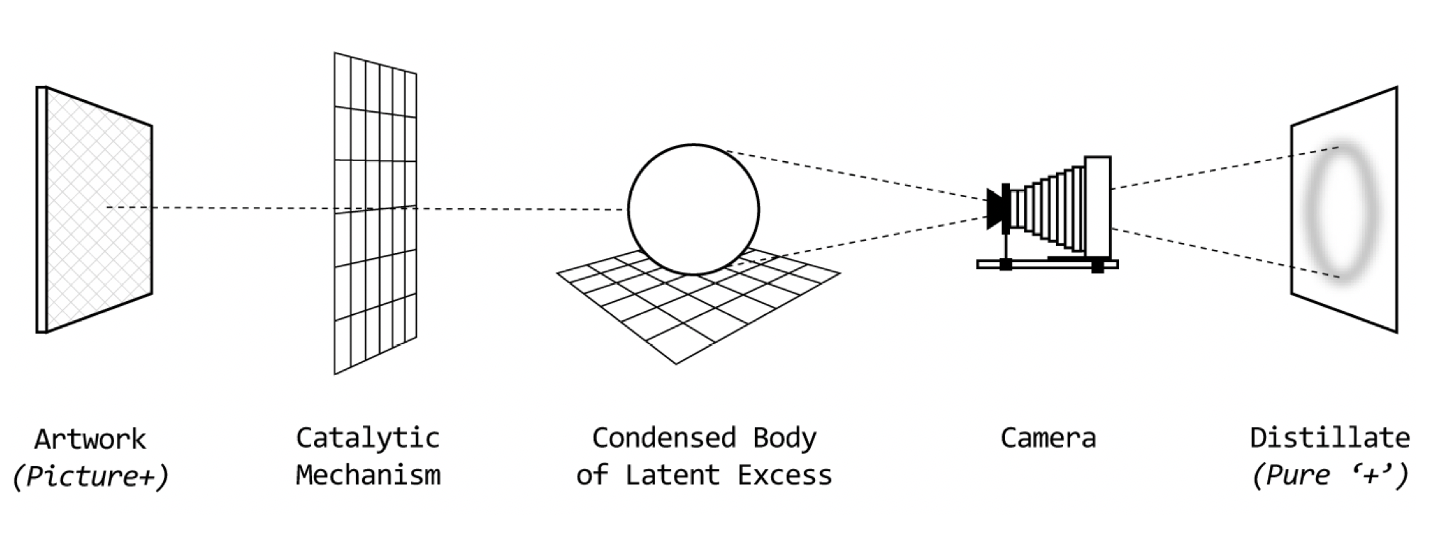

The mechanism was devised; a three-stage process through which the surplus could be distilled from its secondary state, its latent qualities then encapsulated in a material body, before being reinstated to a finally liberated image-state. The methodology bore parallels to the perspectival processes of renaissance art, such as those enabled by Dürer’s drawing machine (fig.vi), though, whereas there the aim would have been to transpose the three-dimensional forms of reality onto the two-dimensional pictorial plane, here the motive is one of severing the un-dimensional trait of the formless excess from its pictorial ties, in order that it might be returned to a transfigurational state of unbounded ground.

The specimen, the work of art or picture+, would be subjected to a process of extraction by means of a catalytic device, by which its immanent excess could be condensed into a three-dimensional form. This body would be engineered by mechanical means, without subjective intervention contaminating its birth from the realm of the artwork’s autonomy. This form would not itself be an embodiment of the distinct, for, as a formed thing, its formless manifestation could only be there in its latent immanence. However, this latent state mirrors that of the photograph, the two things being unbound from formation, instead bound to the formless ground of the real. By way of this alignment, pure image might be induced, the alchemical process complete, by means of the camera’s looking past, missing, the intermediary form, and imbuing the distilled ‘+’ with presence. What was there fully becoming here.

A simplified schematic is all I shall here provide (fig.vii), for refinement of the precise systems at play is ongoing. At this time the mechanisms are such that they are not yet completely freed from the encirclement that binds them away from the desired source, instead eventually bringing about the excess’ ontological collapse. However, the process, one that is ultimately tied to Gödelian mandates, must at some stage happen upon a mode that permits the whole, a completing of the circle, whether this might be in the then, or the here.

figure vii: Extraction and distillation of the autonomous excess of art

![]()

We create our stories, our realities, out of our desires, but great discrepancies become apparent when our choices are subjected to the scrutiny of logic. Love for example, for Lacan, is a form of disfiguring violence: “I love you, but, because inexplicably I love in you something more than you—the objet petit a—I mutilate you” (Lacan 1977b, 263). Art, however, exists on a plane uniquely unbounded by external formations, instead embodying an unparalleled plasticity that brings about the freedom to operate throughout and within all modes of being. Our relations to the objects of art are, by definition, entirely founded upon the subjective mode to which thought is knotted. Likewise, the condition of our relation to language cannot be considered to be anything other than of our own making. There exists nothing but a fabric of singular actuality, but our desire for delineation leads us to construct a fiction of differentiation that, by default, we are obliged to embrace with open arms. It is art’s role to seek the unification of the subjective self with the singularity of the formless, in order that its true presence may be thrust forth. Art—Freedom—is the space in which the more than may be universally accepted.

We may well individually fail to effectively locate that autonomous element of art, as an articulation of such a process is indeed beyond our vocabulary. As such, we may only revert to the fiction of this trait within the constraints of language, one that can never align itself fully to the whole. However, the actuality of that elusive excess may be universally sensed outside of language. Art straddles the constructed amalgamations of appearances and the yet to be formed matter of within. The artist oscillates between the boundaries of these two existences, lead by a compulsion to bring into the world a space that would surpass the world itself. W’s traces are thus the rarest of things, for they may guide us towards an immanent state of absent knowing, a realisation of the formless, through which we must surely pass with silent grace.

[1] Whilst I have previously noted that abstraction acts as an obversion of the real, here the direction of such action is visualised to be perpendicular to the plane of the formless. However, it would be more appropriate to conceive of the sphere of the formless as a singular field—something akin to a Klein bottle—wherein an action towards the exterior and beyond is one and the same as that directed inwards. In this diagram, I would imagine that such a representation has not been adopted due to the complexities of such a visualisation that, though potentially furthering the accuracy of the illustration, might have rendered the schema totally indecipherable.

[2] Or, as Slavoj Žižek puts it, “the whole of reality, it’s just it—it’s stupid!” (Žižek!, 2005)

[3] For a rather (satisfyingly) inconclusive consideration of such matters, refer to ‘Seeing-as, seeing in’ (Wollheim, 205-226).

Bibliography

Bataille, Georges, et al (1995) Encyclopædia Acephalica. London: Atlas

Blanchot, Maurice (1989) The Space of Literature. New England: University of Nebraska Press

Bois, Yve-Alain & Krauss, Rosalind E. (1997) Formless: A User’s Guide. New York: Zone Books

Borges, Jorge Luis. (2000) The Aleph and Other Stories. London: Penguin

Brockelman, Thomas (1996) ‘Lacan and Modernism: Representation and its Vicissitudes’ in Disseminating Lacan, edited by David Pettigrew & François Raffoul, 207-238. New York: SUNY Press

Bruce, Colin (2004) Schrödinger’s Rabbits: The Many Worlds of Quantum. Washington: Joseph Henry Press

Deleuze, Gilles (2004) Difference and Repetition. London: Continuum

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix (2004) A Thousand Plateaus. London: Continuum

Derrida, Jacques (2001) Writing and Difference. London: Routledge

Didi-Huberman, Georges (1995) Fra Angelico, Dissemblance and Figuration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Didi-Huberman, Georges (2005) Confronting Images. Pennsylvania: PSU Press

Fried, Michael (1998) Art and Objecthood. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Fried, Michael (2008) Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before. London: Yale University Press

Foster, Hal (1996) The Return of the Real. Massachusetts: MIT Press

Gidal, Peter (2008) ‘Endless Finalities, Part II’ in Gerhard Richter: 4900 Colours, edited by Melissa Larner, Rebecca Morrill and Sam Phillips, 87-100. London: Hatje Kantz

Hartley, George (2003) The Abyss of Representation: Marxism and the Postmodern Sublime. London: Duke University Press

Heidegger, Martin (1978) ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’ in Basic Writings: Martin Heidegger, edited by David Farrell Krell, 139-212. London: Routledge.

James, Ian (2006) The Fragmentary Demand. California: Stanford University Press

Kemp, Martin (1990) The Science of Art: Optical themes in western art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. London: Yale University Press

Lacan, Jacques (1977a) Écrits: A Selection. London: Routledge

Lacan, Jacques (1977b) The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-analysis. London: Karnac

Lacan, Jacques (1988) The Seminar: Book II. New York: W. W. Norton

Milovanovic, Dragan & Ragland, Ellie, et al (2004) Lacan: Topologically Speaking. New York: Other Press

Nancy, Jean-Luc (1993) The Birth to Presence. California: Stanford University Press

Nancy, Jean-Luc (1997) The Sense of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Nancy, Jean-Luc (2005) The Ground of the Image. New York: Fordham University Press

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1917) Thus Spake Zarathustra. New York: Random House

Scudieri, Magnolia (2004) The Frescoes by Angelico at San Marco. Italy: Giunti

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1974) Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. New York: Routledge

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (2001) Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Wollheim, Richard (1980) Art And Its Objects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Zepke, Stephen (2005) Art As Abstract Machine: Ontology and Aesthetics in Deleuze and Guattari. London: Routledge

Žižek, Slavoj (1991) Looking Awry. Massachusetts: MIT Press

Žižek! (2005) Dir: Astra Taylor, DVD. New York: Zeitgeist Films