Locked Room Scenario, an exhibition constructed within an exhibition, could most certainly be regarded as ‘meta’, but is there also a metamodernist sensibility at play?

I must confess, I came to see Ryan Gander’s show rather late on during it’s two-month long run. I had by this stage read many a review of this, the latest in a long line of ambitious Artangel commissions, and so knew roughly what to expect from my encounter and what I might take away from it. Or so I assumed.

The scenario in question involved making an appointment to visit a Hoxton warehouse, a space called the Kimberling Gallery housing an exhibition entitled Field of Meaning, purportedly by a group of seven Fluxus artists known as the Blue Conceptualists. Only, as I was by now well aware, the entire show had been staged, the fictional construct of Gander’s imagination. Not only that, but, as the title suggests, the main gallery space had been rendered quite literally impenetrable, its doors securely locked, leaving visitors able merely to negotiate their way around its peripheral corridors and backrooms. The occasional glimpse through a gap in the shutters; a rummage around a neglected storage space; a barely audible voice overheard above the gents’ cubicle; these fractured viewpoints are all one is permitted in order to assemble some kind of picture of what lies within. Or, more accurately, to imagine what might have occurred, for throughout the experience, there is a strong undercurrent that suggests something has happened, that something is awry. Piecing together the clues, Gander has made his audience the protagonists in a kind of Poirot-esque mystery, and the whole affair certainly promises much for the curiosity inclined.

As I approach the gallery, however, I wonder whether the fact of my already having this information at hand will be to the detriment of my experience of the exhibition. I recall reading about a recent study carried out into the effects that so-called ‘spoilers’ have on our experience of stories. Rather surprisingly, its results suggest that stealing a premature peek at the last page of a whodunnit novel might, it turns out, actually serve to enhance a reader’s enjoyment of the story rather than ruin it. Similarly, the act of re-watching a favourite film again and again can heighten, not diminish, the joy derived from the unravelling plot. This seems to resonate with a metamodernist mode of thought, since prior knowledge of one’s start and end points can serve to liberate, to let imagination roam free in the in-between, enabling a richer exploration of the territory found therein. Furthermore, might we not also take pleasure in repeating a task (reading a book, watching a film) as if the ending could somehow be different each time, knowingly indulging our futile desire to shape the outcome, and perhaps uncovering unexpected depths along the way?

With this in mind, I set about exploring the grounds of the exhibition. The first fragment I notice is a page from a newspaper, with a passage detailing funeral arrangements having been circled in pen. An ominous start, perhaps? I soon find a way to peer into the inner gallery space, and am confronted with an eclectic selection of artworks of various shapes and sizes. There are black and white photographs on the walls, small text-based projections on the floor, a giant furry amorphous monster in International Klein Blue standing guard in the centre of the room. The overriding sense is of a particularly incoherent group show. I make my way to a foyer area, surrounded by abandoned boxes of postcards of the artists’ works. Sifting my way through, I start to piece together a chronology of the Blue Conceptualist movement, which supposedly had its heyday back in the 1970s, and, according to a press release I come across, “has been hugely overlooked in recent years” (with good reason, one might assume). Most of the included artists are now, it seems, in the autumn of their lives, and the spectre of death certainly hangs heavy in the air. Indeed, I learn that two of the artists are recently deceased, one of whom the previous newspaper clipping was clearly referencing.

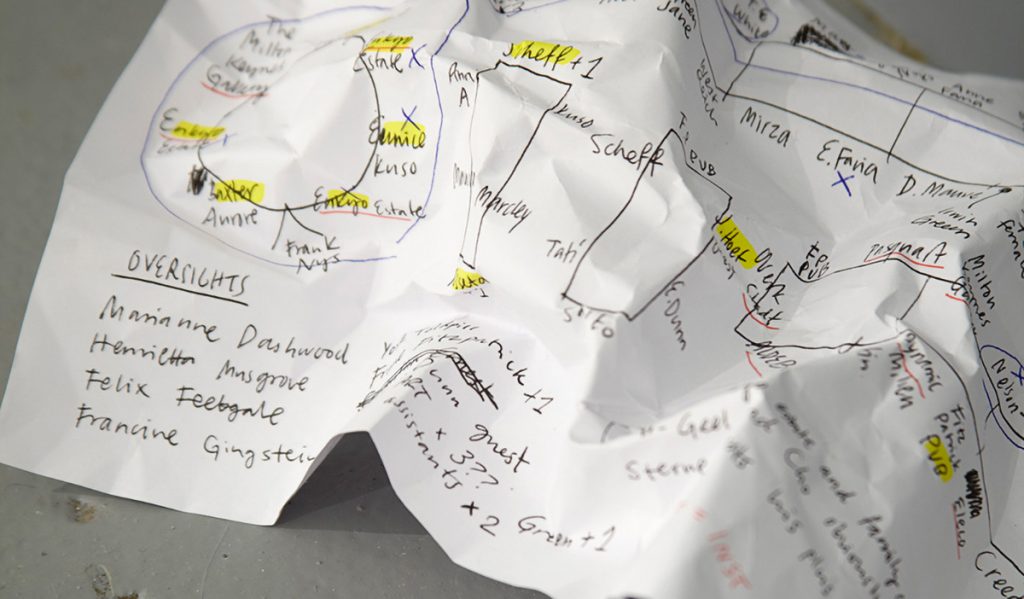

There is a slight but undeniable thrill to be had at each new discovery, as one attempts to knit together the fragments into some kind of coherent narrative. Outside, a skip contains a discarded length of the shaggy blue fabric used to make the sculpture encountered earlier, the unavoidable absurdity of which is contrasted with a melancholic air of failure. Gander humourously reminds us that a lifetime spent seeking artistic purpose, perpetually overlooked, might always fall victim to the scrapheap. Further along, I begin to unearth a tale of love lost, with the words “Mary Aurory Sorry” graffitied on a nearby wall. A little more detective work reveals Mary’s jilted lover to be an artist called Spencer Anthony, a fellow member of the Blue Conceptualists. The plans for an opening evening banquet, found discarded on a staircase, shows signs of having been hastily amended to ensure Spencer and Mary are seated well away from one another. A scrap of paper dropped by a stranger in front of me expands on the theme, the words “Marie Aurore Sorry” cropping up once more.

The corridors and partially obscured rooms of Gander’s productionmight seem rather barren on first impression, but the closer one inspects its palimpsestic surfaces, the more the subtle attention to detail and richness of the staging rewards the viewer. The gap between fiction and reality becomes ever more blurred, as one is forced to question whether the other visitors might in fact be actors. I am reminded momentarily of Mike Kelley’s nearby exhibition at the Gagosian gallery, which would seem to be almost the antithesis of Gander’s immersive experience. Although both artists’ works are concerned with constructing fictional worlds, Kelley’s brand of especially vapid postmodernist excess does not seem to warrant anything more than superficial scrutiny.

Exploded Fortress of Solitude sees Kelley attempt to recreate Kandor, the birthplace of Superman as described in the eponymous comic book series. The futuristic city was, the story goes, shrunk to a miniature scale by the intergalactic supervillain Brainiac, left to be preserved under a bell jar in Superman’s sanctuary, the Fortress of Solitude. As the city has been represented inconsistently in print throughout the years, Kelley has taken it upon himself to produce twenty versions of this hermetic world based on the varying descriptions he encountered. Cast in resin, presented beneath tinted glass, the resultant sculptures appear to be decorated with the kind of unloved shiny plastic knick-knacks that one might pass over at a particularly disappointing car-boot sale. Like a sprawling mass of glowing jelly candies, his cluttered forms are too overwhelming, too saccharine to appeal to anything but the most juvenile of palates. Very little of intellectual or visceral depth can be taken away here, the metaphor of dystopian disconnect wearing thin all too rapidly. Kelley would seem to think that art’s ambition should be to treat the viewer like the proverbial kid in a candy store, a mentality that is symptomatic of the final death throes of the ‘clusterfuck aesthetic’ embodied by Kelley, Thomas Hirschhorn, Paul McCarthy et al. Art’s audience is by now very much grown up, a fact that a younger generation of artists are not afraid to acknowledge, and Kelley’s efforts act only to highlight the strengths of the strategy of understated depth deployed by Gander.

Back at The Locked Room, a block of handwritten text catches my eye, peering out from behind a pane of glass in one dimly lit corner of the warehouse. I notice the occasional letter circled in red. More clues perhaps? I take out my notepad and begin the task of attempting to solve the cryptographic conundrum. After a not inconsiderable length of time spent methodically jotting down each highlighted letter (much to the amusement of my friends, it must be said), I think I have it cracked. But what has been uncovered, what revelation so befitting of such elaborate concealment? I read the letters back to myself: ‘be for ehep assed hes’…? I give it another go: ‘before he passed he said the work was empty’.

At this moment, I feel at once deflated and delighted, finding a validation of what had been suspected all along. There is ultimately no kind of transcendent meaning to be found in the work here (be it that of Gander or his fictitious Blue Conceptualists). However, the space between the split-levels of creation and meta-creation has in this instant been collapsed, and the realisation of such is in itself somehow peculiarly affecting. Much as I had hoped to uncover some astounding or epiphanic nugget of truth, I must have known all along the absurdity of such a desire.

The detritus of a tangled web of failed individual endeavours and interpersonal relations might be all that remains of the Blue Conceptualists’ self-aggrandising, heroic artistic movement. On the other hand, Gander’s own unassuming public persona seems totally at odds with the visionary nature of the artistic collective he has dreamt up. His trick here, however, is to use these opposing personas to bring to life a wide spectrum of associations and desires, to enable an oscillation between positions, and to instigate a meditation on the subject of art’s bind with the human condition itself. What is revealed here, with both humour and gravitas, is perhaps a manifestation of the quotidian sublime; a series of mysteries of very human proportions, born out of the simultaneous futility and liberation that the aforementioned emptiness proclaims. Neither Gander’s ‘own’ voice, nor those of his fictional characters, can be said to offer up any kind of solution. In a sense, the locked room is whatever each viewer makes it, and as such, its darkest recesses will surely remain forever hidden from view. As a metamodern spectator, however, we can take great delight in attempting to unmask that which lies between and beyond, and you never know, things might just turn out differently next time.

Photos: Julian Abrams, courtesy Artangel